Issue of the Week: Hunger

The End Of Civilization As We Knew It, Part Thirty Three

The author of this post is sitting on a plane returning home to Seattle from Ukraine via Warsaw.

We take a break from Ukraine as the sole topic of the last two posts and as the project we will be working on with film and images and interviews and experiences, intensely, for some time, in producing a documentary from this journey.

Today, appropriately, we return to the issue that our work began with and has continued to be a critical part of for decades.

World Hunger.

There is a searing part of this issue of crucial importance related to Ukraine as well, which we will get to later in this post.

As written about and shown in our productions for years, the issue of world hunger was chosen as our initial focus because hunger killed, and still does–even though greatly reduced because of our work and the work of many, many others–more people, mostly children, than anything.

And because it used to be the one thing that everyone agreed should be ended (they just needed focus on how it could be). It was the one non-polarizing issue, with strong support for programs to help, from Republicans and Democrats alike, that also had the benefit (or hazzard) of being interrelated with and necessary precondition to solving every other problem that threatened humanity.

Yesterday was World Food Day. Like all such days, once filled with real focus, it’s a day now that passes without even being noticed by most people. A sign of our times. The complete collapse of our moral, ethical, community culture built on any meaning that had boundaries of behavior and action that could be counted on, in America and globally.

Whose fault is that?

All of ours.

Whose responsibility to change?

All of ours.

The historical and sociological reasons for our current condition have been covered extensively by us and others.

The bottom line we refer to now is that without a guarantee of basic needs for all people, we are doomed as a species. So even if you don’t care about anyone else, you need to act like you do if you want to survive.

Are you going to stop letting babies and children starve and die and be maimed and stunted by disease? We have talked often about child abuse, of which this a form. We will end it, or it will end us.

When it comes to basic needs for survival, if you are going to let babies and children die and have their lives destroyed, then stop hiding and say it and defend why publicly.

Good luck with that.

You may believe that guaranteeing basic needs for all adults is a mistake for all the usual reasons put forth by the handful of people who own everything and have convinced others they are fleecing that they (and others less able and they believe less deserving than them) should be fleeced if they don’t pull a rabbit out of a hat and find a job, if there is one, that pays more than it does, while a home can’t be afforded by even the hardest working people, and so on. Government (which is to say all of us) shouldn’t provide any security for basic needs for others.

If so, you should give back your Social Security and Medicare and health care and not notice that there are or have been systems in American history with financial regulations, high taxes for the rich, who barely noticed and would even less with their extreme wealth today, functioning unions, good paying jobs, affordable housing and the biggest most prosperous middle class in history. And systems and policies in the world that have and do provide the combination of basic guarantees and work to achieve more, that are prosperous and democratic and sustainable, if always in need of adaptation to do better, as is the state of human affairs.

But regardless of your views on what should or should not be guaranteed in terms of survival for adults, the simple fact is that babies and children have parents and caregivers and teachers and on and on–adults they need to survive–who can’t be there for them with any certainty unless their survival is guaranteed as well.

This is just shorthand, purposefully, to make a point.

Start with the babies and children. Give them life or kill them, give them basic needs or deprive them and maim them and stunt their growth in every way. Billions are being killed and stunted for life physically and mentally. If you can live with that, please leave earth.

If you stay (the above is not a call to suicide for the sociopathic–so unless you’re among the handful riding away to the brave new AI world on Mars with Elon from the earth and humanity you’ve destroyed, you will stay), the children will become adults costing infinitely more to society, to you, with all the costly problems they have in their suffering. And in the end they will be coming after you with pitchforks.

Oh wait, that’s right, it’s a world now of nuclear weapons, and more.

So in that world, and as the prime example of the end of all civilized or even international, national and personal survival behavior, after the US election last November, Trump, the Republican congress (no real Republicans left but a handful, just cult followers of what David Brooks has described as a gangster enterprise), and the corporate titans (the richest one in particular) destroyed the entire global US aid system in place since World War Two. Officially organized as USAID by President Kennedy, it was strengthened by every Republican and Democratic president and congress since, especially after Jimmy Carter made ending hunger a priority after seeing our first film on hunger. It was a bookend irony of all times not recognized by us when we covered Carter’s state funeral, that days later Trump would be sworn in on the same spot in the Capitol Rotunda.

What precious little is left of the remnants of USAID and other aid programs has been transfered to the state department, and the claim has been and is made performatively by the Trump administration, that no harm has been done. The administration claimed USAID has little to show since the end of the Cold War.

Well, as John Adams (arguably the most important figure in the American Revolution–and since what was commonplace knowledge is a black hole these days, your responsibility as a sentient being is to look up, learn and study what you don’t know) reminded us:

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

Not exactly a saying for our times, which underlines the irrefutable point of it.

To point, just this last July, a study published in The Lancet (one of the most reputable medical journals in the world–the following is too important to wait for anyone to look it up as intoned above) estimated that 14 million people would die, including 4.5 million children, in just the next five years because of the USAID shutdown.

With the rise in population in the places most in need and historically served, the numbers of millions of deaths will rise exponentially. Probably far above a hundred million in two decades.

For the psychopaths disguised as realists, this will not equate to a population offset by thinning the herd. All factors considered plus the dynamics behind population growth in the most impacted countries, this will add to population. Plus in any event, all this will be a match to light instability into a global bonfire. What goes around, comes around, with a fury.

The same study estimated that over 90 million lives had been saved by USAID over the past two decades. Since the end of the Cold War that would be about 158 million lives saved.

Well, who could argue that saving 158 million lives was “little to show”?

Ambassador W. Robert Pearson was the ambassador to Turkey under President George W. Bush (the Republican president liberals and progressives most loved to hate in recent years, often called “Hitler,” until Trump came along) and director general of the US Foreign Service from 2003 to 2006 (also during the Bush administration).

In an article in American Diplomacy in August, titled “The Destruction of USAID: How to Cause Innocent Deaths, Save Little Money, Betray Our Legacy and Help Our Adversaries”, Pearson wrote:

The final destruction of USAID by President Trump in early July 2025 is the greatest strategic surrender of global American influence in the 80 years since the end of WWII.

Section titles such as Millions of Deaths – Microscopic Budgetary Gain and Our Adversaries are the Winners speak for themselves.

During the Cold War, USAID helped win it. When people in the “huts and villages of the world”–as JFK famously spoke of in his immortal innaugural address in 1961–thought of who was bringing them food, medicine and developmental help, it was America. It was pictures of JFK on the walls after his assassination for years in such places, not any Soviet leader.

USAID was a major collaborator in the global campaign to eliminate smallpox, which was eliminated as a disease in 1979.

It had killed 500 million to one billion people throughout history, including 300 million in the 20th century.

It is the only disease that has ever been completely eliminated–by a vaccine, or hundreds of millions more would already have died.

Along with PEPFAR, the program created by President George Bush, USAID was in the process of potentially eliminating HIV/AIDS, saving millions of lives mainly in Africa. The funding has nominally been partly spared, but the impact when USAID was shut down was, and has been, catastrophic.

As the Cold War was in the process of ending, USAID played a crucial role in supporting movements and programs that supported democracy and stability in a crucial time of transition, helping to make and maintain America as the only superpower in the world, and spread global democracy peacefully more than at any time in history.

The Democrats have been feckless in terms of any sustained focus on this issue, even while talking about the crumbling of democracy. Yes, the term foreign aid has often not been all that popular. But specific support for ending hunger and disease and providing these kinds of basics for people in need around the world has always been popular with the American people. Talking about the results of the destruction of services for Americans, including those that prevented hunger in America for infants, children and mothers, and particularly the threat to health care for all Americans, has been useful. But the opportunity to continually keep eyes on the responsibility for maintaining America’s security and moral place in the world instead of enabling dismantling it have been woefully wanting.

And most responsible?

The majority of Americans who at least have the basics themselves.

A majority of American adults may act like babies whose attention span doesn’t go beyond the next want and feel-good cultural addiction and ideological knee-jerk reaction, but they’re adults. And when they saw the headlines about USAID and the unprecedented damage to humanity it would cause–death for millions and danger in a chaotic world–they had an absolute responsibility to pay attention, and tell their president and senators and representatives to stop it, immediately, or this thing called political payback would hit them like a tsunami.

A related and insidious event that has occurred in the wake of US demolition of its aid programs is the substantial reduction of such programs by Western European NATO countries. These countries, such as the UK, which have been in the forefront of championing such aid for years, have done and are doing so because of insistance by the Trump administration that they spend more on defence related to NATO.

This is worse than mixing apples with oranges. Increasing defense spending for NATO in the face of the Russian threat from the war in Ukraine and increasing provocations in Europe is definitely needed, ironically because the European nations have no confidence in being able to count on the very US administration insisting on it. But here’s what you get from that:

A moral migraine that never goes away. Increased instability and conflict in the nations suffering from hunger and poverty. Directly resulting in more desperate migrants coming to your countries. Creating financial strain and more importantly political polarization in your own nations as a result.

But with Putin coming at you from one side and Trump breathing down your neck from another, there’s no real choice, except of course to do what the US should do–get more tax income from the super rich.

But the economics of scale on this issue are weighted 90-plus percent as a responsibility of the US, which should be behaving this way in its own interest in any event. If Europe is going to carry a heavier defense burden, then the US should be adding to aid programs, not destroying them, to make up for any cost to aid programs from Europe.

The US can easily afford it. The US has by far the largest GDP in the world. The national debt problem, which is real, has been caused by a number of things. The so-called DOGE project by Trump under Elon Musk saved virtually nothing in percentage by gutting USAID and other important services. The moral and national security costs of doing so are the definition of insanity. The money saved by trashing USAID couldn’t even be meaningfully statistically measured by percentage in comparison to the tax cuts for the rich and super-rich in the first and second Trump administrations. We’re talking trillions. And trillions to the national debt so a handful of people can own the rest of the wealth in the world they don’t already. The billionaires and multimillionaires were already in tax heaven before this insane socialism for the rich happened. Trillions to the national debt and suffering to Americans in services lost and increased inequality beyond an inequality already unimaginable before. But when no one has really delivered for the working class, divisive rhetoric works for a while until reality becomes clear.

A widely praised proposal–as just one example to make the point–for ending the most extreme aspects of inequality and ending hunger and poverty in the world, is that all billionaires pay a 2% tax. They might turn scarlett red and have blood veins burst in their “philosophical” outrage, but obviously, if someone picked their pocket of this infinitesimally small amount, they’d never notice.

But millions of children living instead of dying would.

In Ukraine, and every other recent place globally visited, we’ve been told of the devastating damage by the end of aid from USAID.

In February, the World Food Programme reported:

As the war in Ukraine enters its fourth year, an estimated five million Ukrainians are facing food insecurity, with the greatest needs concentrated in areas near the frontlines. According to data collected by the UN World Food Programme (WFP), millions of people are resorting to coping mechanisms, sacrificing their own meals so their children can eat. Others are going into debt to buy sufficient food supplies to feed their families.

WFP continues to provide food and cash assistance to nearly 1.5 million Ukrainians each month, mostly in the frontline regions. Despite these efforts, more than half of the people in the Kherson region in the south face severe hunger, and, two out of every five individuals face hunger in Zaporizhzhia as well as the Donetsk region in the east.

In a report two days ago, “UN’s World Food Program warns donor cuts are pushing millions more into hunger,” WFP said it expects to receive 40% less funding this year, largely due to slashed outlays from the U.S. under the Trump administration, which “could amount to a death sentence for millions of people facing extreme hunger and starvation”, said WFP.

According to the UN, 14.6 million people in Ukraine need humanitarian aid, 5 million are internally displaced and a third of the population faces food insecurity.

NGOs based in and outside of Ukraine providing food and other humanitarian aid have reported drastic reduction in their ability to provide services as a result of USAID shutting down.

Action Against Hunger reports:

CONSEQUENCES OF THE U.S. FOREIGN AID FREEZE IN UKRAINE

As Ukraine marks three years of war, the U.S. government’s suspension of international aid has caused Action Against Hunger to stop distributing cash to families displaced near the front line. Humanitarian operations in the region were already functioning with limited resources and struggling to access frontline areas.

Just a week and a half ago, we met with and interviewed on video three extraordinary women in Kyiv who had leading roles in two major NGOs dealing with providing humanitarian needs for 2.8 million internally displaced persons from Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, and the abduction, trafficking or forced attempts to erase Ukrainian identity of 1.6 million Ukrainian children by Russia. At this point we’re not naming people or organizations we dealt with in Ukraine while we wade through countless hours of video to produce a documentary on the above.

Among those needing emergency help are those who live through their homes being destroyed by Russian air strikes or are driven from their homes by Russian air strikes and brutal occupation of Ukrainian territory.

At one point in the interviews of all three of the above Ukrainian women who have lived through the Russian air attacks along with nearly all civilians in Ukraine almost daily for three and a half years, we asked the question: What has the impact been of shutting down USAID?

Heads and faces and eyes moved in dismay and depression. It came out of nowhere. Sudden. Never seemingly possible. And it has been disastrous for the wounded and suffering people they serve.

What were the top ten countries receiving support from USAID (last report from fiscal year 2024) when it was shuttered?

Ukraine, Democratic Republic of Congo, Jordan, Ethiopia, West Bank and Gaza, Sudan, Nigeria, Yemen, Afghanistan, and South Sudan.

The other two worst wars in the world in terms of hunger, civilian deaths and suffering are Sudan (the worst) and Gaza, in which hunger and starvation have been rampant and a ceasefire hopefully gives the opportunity to alleviate the horrible suffering there (we are skeptical about the prospects for many reasons to be covered in the future).

As we said a while back, everything is changing.

In the wrong way.

And it needs to stop.

Four days ago, after arriving in Warsaw from Kyiv, we went to the site, museum and memorial at Treblinka, the Nazi extermination camp. It was the second largest death camp in the Nazi Final Solution. Auschwitz was the largest, but there were many who worked as slave labor there before being killed, hence more survivors when the camps were liberated. Treblinka had one purpose. Killing upon arrival. Nearly one million of the six million died there. As haunting an experience as there could be in the universe.

We’ve all seen images of babies dying or severely malnourished, diseased, and if lucky enough to be saved, with many hurdles to come. They look like the images of the inmates at the death camps, those dead and piled to be burned and those who barely were alive when liberated.

The Nazis have been seen as the archetype of evil, which they were.

But what is the difference morally with millions of babies and children starving and being stunted every year, when the resources to change this were and are readily there, and humanity lets this go on? And then the most reliable solution to the emergency part of this and in many ways the sustainable development beyond this, which has saved countless millions of lives, is consciously ended, instantly, unimaginably, by a new American president, congress not even asserting its own constitutional duties, undermining democracy while being architects of human slaughter on a new scale, and the American people enabling it.

The ongoing annihilation of the desperate of humanity, singling them out because they are the most desperate of humanity. The most expendable in service of a facade of saving money for a further tax cut for the richest people in history by far. A new form of pure evil.

But hey, don’t listen to us.

Listen to the pope.

You, know, the new guy on the global scene, the American pope, Leo XIV.

Yesterday, Pope Leo spoke at the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) in Rome on World Food Day about world hunger and accompanying poverty, disease and war. It was covered in all the major media worldwide.

Leo has moved slowly, still at the start of his pontificate, in being a public presence.

There was no reticence yesterday. He clearly decided that this was the moment to address hunger and all issues related to it as the heart of evil in the world and to pull no punches in demanding that it must be ended as the urgent responsibility of everyone:

. . .

“Eighty years after the establishment of the FAO, our conscience must once again challenge us to face the ever-present tragedy of hunger and malnutrition. Putting an end to these evils is not solely the responsibility of businesspeople, civil servants or political leaders. It is a problem that we must all work together to solve: international agencies, governments, public institutions, NGOs, academic institutions and civil society, not to mention each individual, who must see the suffering of others as their own.” …

“This crisis should immediately engage our attention and lead us to redouble our individual and collective responsibility, awakening us from the fatal lethargy in which we are often mired.” …

“At a time when science has extended life expectancy, technology has brought continents closer together and knowledge has opened up previously unimaginable horizons, to allow millions of human beings to live – and die – in the grip of hunger is a collective failure, an ethical aberration, a historical shame.” …

“We cannot aspire to a more just social life if we are not willing to rid ourselves of the apathy that justifies hunger as if it were background music we have grown accustomed to, an unsolvable problem, or simply someone else’s responsibility. We cannot demand action from others if we ourselves fail to honor our own commitments. By our omission, we become complicit in the promotion of injustice.” …

“How can we explain the inequalities that allow a few to have everything and many to have nothing? … Ukraine, Gaza, Haiti, Afghanistan, Mali, the Central African Republic, Yemen and South Sudan, to name just a few places on the planet where poverty has become the daily bread of so many of our brothers and sisters?” …hunger is a collective failure, an ethical derailment, a historic offence. … do future generations deserve a world that is incapable of eradicating hunger and misery once and for all? …hunger is not humanity’s destiny but its downfall.”

. . .

Following are three extraordinary articles in The New York Times and Associated Press today on the unprecedented horrors caused by the destruction of USAID and destruction or reduction of other aid programs, such as the FAO and the World Food Program.

The first lengthy article is a master class in the evil of this destruction.

The last is another heartbreaking take on the same evil.

The second is a fully immersive shaming to all Americans and all people in the world who are not doing everything they can. People who have lost all means of support by losing the aid to be caregivers returned to do the caregiving work for nothing, while they have nothing, in response to the most horrible suffering being caused.

They are the human beings. We who have caused and abetted this are the desperate souless ones.

America’s Retreat From Aid Is Devastating Somalia’s Health System

Hunger and the diseases that stalk small children have surged in Somalia after the U.S. slashed its aid to the country.

Listen to this article · 12:01 min Learn more

By Stephanie Nolen, The New York Times

Photographs by Brian Otieno

Stephanie Nolen and Brian Otieno visited the city of Baidoa in southern Somalia and surrounding camps for displaced people to report this story.

- Oct. 17, 2025

The mothers arrived at the emergency feeding center all day long, their faces tight with anxiety, their children limp in their arms. Nurses quickly weighed each child and checked for infection. The frailest were given tubes threaded up their noses and down into their bellies, for a slow drip of fortified milk. Those a little bigger were placed in a bed in a packed room for feeding with therapeutic peanut paste. The ones with rashes, fevers and deep, hacking coughs — potential diphtheria, measles, whooping cough, maybe cholera — were tucked into bare isolation rooms.

It wasn’t like this even six months ago.

Here in Baidoa, a city in southern Somalia, community health workers used to go door to door looking for children who were too thin or sick. Care was swift, and free, at rudimentary clinics set up in camps and neighborhoods. Families received parcels of special foods packed with nutrients. As a result, it was rare for children to deteriorate to the point they needed to be transported to a center for 24-hour care.

But the community health clinics, and emergency food, were paid for by the United States, through its Agency for International Development. When the Trump administration dismantled the agency and ended vast swaths of foreign assistance to the world’s poorest countries, much of the food aid and health care for children across Somalia were abruptly cut off.

So now more children are arriving at emergency centers, and they are sicker and thinner than ever. Their vertebrae poke like the teeth of a comb through the translucent skin of their backs.

The swift American exit from Somalia — a country gripped by twin menaces of recurring drought and Islamist insurgency, where the United States has long seen a strong geopolitical reason for partnership — has created chaos all through the country’s health system.

The aid organization Save the Children was operating 128 community health facilities across Somalia, and had to close 47 of them in March, leaving more than 300,000 people without health and nutrition services. The International Medical Corps closed medical centers in four regions of the country, including Baidoa, a sprawling, sun-bleached city of 750,000 hosting some 770,000 displaced people. U.S. support for the United Nations’ World Food Programme, which supplies fortified milks and therapeutic peanut paste for malnourished children, was reduced.

The United States sent an average of $450 million a year in humanitarian assistance to Somalia over the past decade, including $481 million in 2020, the final year of the first Trump administration. Internal State Department data reviewed by The New York Times shows that in the 2025 fiscal year, which ended on Sept. 30, about $128 million had been sent to Somalia.

The State Department said on Oct. 9 that the Trump administration had approved $14.9 million in funding for Somalia. In an emailed statement, it said both military and humanitarian assistance to Somalia continued.

“The United States remains committed to working with Somalia to counter terrorist threats and address shared security concerns,” the statement said.

The United States has been by far the largest donor to Somalia, and the Trump administration has argued that the United States has been contributing more than its fair share of aid around the world. “The State Department will continue its mission to encourage other donors, including governments and the private sector, to come up with sustainable solutions for those most in need,” the statement said.

Dr. Binyam Gebru, Save the Children’s director in Somalia, and his colleagues had to make agonizing choices after the U.S.A.I.D. grant they had received for the past eight years, which averaged about $15 million a year, was not renewed. In Baidoa the organization ran a feeding program that delivered fortified food to all the children and pregnant and breastfeeding women in the vast camps of displaced people that surround the town. Either the community feeding program or the emergency centers would have to shut down.

They could stave off severe illness — and a lifetime of cognitive and physical impairments — for many more children if they maintained the community feeding program, which costs much less than inpatient emergency treatment. But for the sickest children, the emergency center is the difference between life and death.

“Of course lifesaving intervention should be prioritized, and that’s what we have done,” Dr. Gebru said. “But it’s devastating. You know that in the community, you could treat a child for a few dollars, and very quickly.”

Save the Children has even had to close some emergency centers; the organization has tried to maintain at least one in each region.

In the aftermath of the United States’ exit, Somalia has seen a decline in funding from other countries, too. “Most of our key donors — the Dutch, the Germans, the Brits — it’s all coming down,” said Crispen Rukasha, the head of the U.N.’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Somalia. Britain was the second-largest donor to health in Somalia, but will end its funding for health care in March.

The World Food Programme said that starting next month, it would be forced to reduce the number of people who receive emergency food assistance in Somalia to just 350,000, down from 1.1 million in August — fewer than one in every 10 people who are in need of food aid for survival.

The need for help is intensifying: the grip of the drought has been growing each year. A quarter of Somalia’s 16 million people are displaced. In September, a U.N.-backed group of experts who monitor world hunger upgraded its level of warning for Somalia, saying 3.4 million Somalis were experiencing “crisis” levels of food insecurity and that the number would most likely increase by a million people by the end of this year.

The area around Baidoa once produced half the country’s food, but 34 years of civil war has destroyed farms. Dr. Gebru said that in the past, his organization has been able to direct resources into hard-hit communities, and provide a buffer when famine loomed. Now, he said, they can only watch it come.

In a congested camp on the city’s edge, Owliyo Ali has worried for some time that her youngest child, a son, is much too light for an 18-month-old. When his older siblings were babies, she relied on regular supplies of fortified foods that she picked up at the health center a few minutes’ walk from her home. But now that center is closed.

Save the Children mobile teams still come to the camp a couple of times a week for a few hours, but they don’t bring as much food.

“Usually they run out before I get any for him,” she said.

A few weeks ago the child had diarrhea and a high fever, developed a measles rash and grew too weak even to cry. She wanted to take him to a clinic, but the only option now is the hospital in town — a $3 taxi ride away, three times more than the $1 her husband earns for a day’s work. The couple borrowed from neighbors, and the boy was admitted for four days; weeks later, he was still listless and glassy-eyed.

Ms. Ali and her family fled their home eight years ago, after their harvests failed repeatedly. They now live in a shack made of sticks and sheet metal. Ms. Ali is pregnant, and she was also relying on food from the health center. Research shows that in areas with high rates of malnutrition, providing pregnant women with fortified foods can have a significant positive effect on their children’s growth and health. But that food ran out months ago, she said.

At Bay Regional Hospital, admissions for malnutrition were up by 40 percent by July compared with January, said Dr. Abdullahi Yusuf, the facility’s medical director. They used to see children with diphtheria once or twice a year, but there have been 50 cases in the last three months. Children who come are much sicker, he said, and pregnant women arrive with life-threatening conditions.

“Previously we had early referrals, from community health workers — now they come late and the complications are much more severe, and so the deaths are higher,” he said.

Pediatric and obstetric staff members at the hospital are paid for and supplies are purchased by Doctors Without Borders, one of the few organizations which accepts no funding from governments and thus has been able to keep operating. But Dr. Yusuf said the situation was not sustainable: A ward for 50 children sometimes has 90 crowded into it, he said.

Somalia’s national government collected just $350 million in total revenue last year. Almost all of that was spent on security, as the government struggles against two militant organizations that control about a third of the national territory. The government pays for about 4 percent of all health spending in the country; foreign donors cover 60 percent and the rest is out of pocket.

Dr. Ibrahim Adam Somow, director general of the state health ministry, said he and his colleagues were stunned when they began to receive emails from one international partner after another, announcing that their funding had been terminated and they were leaving. Clinics and feeding centers closed overnight.

Keeping skilled staff members to run childbirth facilities has been one of the priorities for spending their limited funds, he said. Keeping at least one outpatient center for children in each area is another.

“Our priority is to reach the child who lives under a tree so that he or she survives and becomes tomorrow’s leader,” he said. Dr. Somow, who recently earned a doctorate in public health, was once one of those children himself: he remembers waiting under a tree to be immunized in a vaccination blitz.

At 40, he’s proof of progress, he said, but Somalia is a long way from being able to cope on its own. “It is like rebuilding a building: everyone must bring a brick,” he said.

Despite the challenges, Somalia had made public health gains in recent years, bolstered significantly by the U.S. funding. The number of child and maternal deaths was slowly falling. Vaccination coverage was creeping up, as immunization teams made forays into areas that had been controlled by insurgents.

“This is a country riddled with crises, and yet amid all this, there were still improvements,” Dr. Gebru said. “Good things were happening. But one such aid cut or one huge crisis will reverse everything we have done for years.”

Now one problem is driving the next, he said: malnourished children are more vulnerable to disease. They are displaced by drought and war, arriving in congested camps where they are packed in next to other underfed children, who also haven’t had the chance to be immunized.

Somalia’s weak state has created openings for actors intent on regional destabilization, a process the United States has historically tried to counter with large investments in food and military aid. An Al Qaeda-affiliated organization called Al Shabab controls about a third of the country’s territory, while an offshoot of the Islamic State has carried out attacks across the country from a base in the north.

The humanitarian assistance served a hearts-and-minds purpose, and bolstered the image of the United States in communities where there had been intermittent U.S. military activity confronting the militant groups.

Nutrition programs also lead to a more stable and prosperous country, said Meftuh Omer, who directs child survival work for Save the Children in Somalia. “The long-term effects of malnutrition are contributing to the conflict: there is cognitive impact, performance in school is poor, then the only option young people face is the easy way of joining a militia,” he said.

Save the Children has used funding from sources such as individual donors to keep some operations in Somalia going, but Dr. Gebru said those funds would stretch no further than the end of the year. Just as food supplies run out, the organization will have to close the last of its emergency centers.

Amy Schoenfeld Walker contributed reporting from New York.

Stephanie Nolen is a global health reporter for The Times.

See more on: U.S. Politics, Save the Children, Agency for International Development, United Nations

. . .

A Somali Hospital Closed After U.S. Aid Cuts. Fired Employees Reopened It Without Pay.

After the Trump administration stopped funding a medical center for women and children, a determined group of health care workers refused to let it shutter.

Listen to this article · 5:39 min Learn more

Photographs by Brian Otieno

Reporting from Baidoa, Somalia

Oct. 17, 2025

In the first week of July, staff members at the Suuqa Xoolaha Center for Mothers and Children, a hospital in southern Somalia, closed its doors and locked its high front gate.

Funding from the United States, which paid for salaries and medical supplies, had been cut by the Trump administration, and the aid organization that managed the hospital fired the doctors, midwives and other workers.

But word of the closure didn’t reach everyone who needed to know. Khadija Ali, 25, arrived at the hospital a few days later, from a camp for displaced people outside the city. She was in the late stage of labor, accompanied by her aunt.

She pounded on the door, crying and saying she was afraid she might die if she could not deliver her child inside. Somalia has one of the highest rates of maternal mortality in the world.

Her labor was too far progressed for them to go anywhere else, her aunt, Habiba Ali, said. And they had no money; this was the only hospital they knew that offered free maternal care. Ms. Ali began to give birth outside the hospital door. The commotion woke neighbors, who carried her into their home, where she delivered a healthy baby girl.

Word of Ms. Ali’s traumatic midnight birth spread quickly among the fired hospital workers.

Khadija Noor Adan, a nurse-midwife at the hospital, was aghast when she heard the story. She resolved that she wasn’t going to sit at home any longer, job or no job, when women were giving birth in the street.

Many of her colleagues felt the same way — and they resolved to reopen the hospital.

“We decided, now it is time to work for the community,” she said. “Despite the fact we have no salary, we feel a responsibility to come to work.”

Word spread, and within days, the employees had reopened the hospital: doctors, mental health counselors, cleaners and the pharmacist. None of them are being paid.

“Whether you get something or nothing, you have to do what you can for your society,” said Abdikadir Hassan, the pharmacist.

The medical center is next to a bustling livestock market on the outskirts of Baidoa, a city of 750,000 that has absorbed an additional 770,000 people displaced by drought and war into makeshift camps scattered around the town.

Learn more about how Stephanie Nolen approaches her work.

The hospital is nominally run by the state government. Officials could unlock the doors and welcome staff members back to work. But like nearly all other health facilities in the country, this one depended on foreign assistance to staff and equip it.

Until January, the United States was the largest donor to Somalia, spending hundreds of millions of dollars each year on health, nutrition, shelter and sanitation projects. Most of that funding was channeled through the United Nations and nongovernmental organizations that provided those services.

Since the Trump administration took office, much of the assistance that flowed to Somalia through the United States Agency for International Development, or U.S.A.I.D., has been cut off, either through terminated grants or through annual awards that were not renewed.

For each of the past eight years, International Medical Corps had received a U.S.A.I.D. grant worth about $10 million to staff and equip the medical center and ones like it in three other districts of Somalia. When that grant ended in July, it was not renewed.

In a statement, the State Department said that both military and humanitarian assistance to Somalia continued but that the administration was “significantly enhancing the efficiency and strategic impact of foreign assistance programs and ensuring that foreign assistance reaches those in need.”

The Trump administration has said that much of the funding that went through U.S.A.I.D. in the past was wasted and that the United States was covering an unfair share of the burden of foreign aid. The United States was by far the largest donor to Somalia.

As word has spread of the lost U.S. funds, patients have worried that the hospital may close for good. “It’s a dilemma in the community — people doubt the hospital will be running,” said Dr. Hassan Adan, the hospital’s acting director. (He is not related to Ms. Adan.) “They say, ‘When will you be paid? Will the facility close?’”

The volunteer staffing arrangement has led to some changes at the hospital: Teams of nurses don’t do mobile outreach any more so that they can cover the 10-bed maternity ward 24 hours a day, and everyone takes an extra day or two off each week.

Some of that time is spent looking for a new job, Ms. Adan said. The reality is that she needs to find a job that can pay her. “If I find a job, I will go,” she said.

She said she supported 10 people on her $536 monthly salary. Dr. Adan said he was supporting 20 people on his, including paying school fees for four siblings. Without his paycheck, they have had to leave school.

“My family is always asking, are you going to get paid?” Mr. Hassan, the pharmacist, said.

The hospital’s director and one nurse have already been hired away to Baidoa’s regional hospital, which is now struggling with an influx of patients who were previously cared for at primary health centers in camps for the displaced, half of which have closed since the U.S.A.I.D. cuts began.

What happens to their medical center when most or all of the staff members are gone?

“That is a difficult question,” Dr. Adan said, standing in a corridor crowded with patients. “It will close. But we hope to continue our work.”

Amy Schoenfeld Walker contributed reporting from New York.

. . .

The tiny African nation of Lesotho had victories in its HIV fight. Then, the US aid cuts came

By Renata Brito, Bram Janssen and Nqobile Ntshangase

October 16, 2025, HA LEJONE, Lesotho

In the snow-topped mountains of Lesotho, mothers carrying babies on their backs walk for hours to the nearest health clinic, only to find HIV testing isn’t available.

Centers catering to the most vulnerable are shutting their doors.

Health workers have been laid off in droves.

Desperate patients ration or share pills.

This Lesotho was unimaginable months ago, residents, health workers and experts say. The small landlocked nation in southern Africa long had the world’s second-highest rate of HIV infections. But over years, with nearly $1 billion in aid from the United States, Lesotho patched together a health network efficient enough to slow the spread of the epidemic, one of the deadliest in modern history.

Then On Jan. 20, the first day of U.S. President Donald Trump’s second term, he signed an executive order freezing foreign aid. Within weeks, Trump had slashed overseas assistance and dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development. Confusion followed in nearly all the 130 countries with USAID-supported programs. Nine months later in Lesotho, there’s still little clarity.

With the single stroke of a distant president’s pen, much of a system credited with saving hundreds of thousands of lives was dismantled.

It’s a moment of chaos and temporary solutions

Weeks ago, the U.S. announced it would reinstate some of its flagship initiatives to combat HIV worldwide. Officials here applauded the move. But the measures are temporary solutions that stress countries must move toward autonomy in public health.

The State Department told The Associated Press in an email that its six-month bridge programs would ensure continuity of lifesaving programs — including testing and medication, and initiatives addressing mother-to-child transmission — while officials work with Lesotho on a multiyear agreement on funding.

Those negotiations will likely take months, and while programs may have been reinstated on paper, restarting them on the ground takes considerable time, Lesotho health workers and experts told AP.

HIV-positive residents, families and caregivers say the chaos that reigned most of this year has caused irreparable harm, and they’re consumed with worry and uncertainty about the future. Most feel deep disappointment — even betrayal — over the loss of funds and support.

“Everyone who is HIV-positive in Lesotho is a dead man walking,” said Hlaoli Monyamane, a 32-year-old miner who couldn’t get a sufficient medication supply to support him while working in neighboring South Africa.

HIV prevention programs – targeting mother-to-child transmission, encouraging male circumcision, and working with high-risk groups including sex workers and miners — were cut off. Unpaid nurses and other workers decided to use informal networks to reach isolated communities. Labs shuttered, and public clinics grew overwhelmed. Patients began abandoning treatment or rationing pills.

Experts with UNAIDS — the U.N. agency tasked with fighting the virus globally — warned in July that up to 4 million people worldwide would die if funding weren’t reinstated. And Lesotho health officials said the cuts would lead to increased HIV transmission, more deaths and higher health costs.

Calculating how many lives are lost or affected is a massive task, and those responsible for tracking and adding data to a centralized system were largely let go.

Lesotho Health Secretary Maneo Moliehi Ntene and HIV/AIDS program manager Dr. Tapiwa Tarumbiswa declined repeated requests to be interviewed or comment about the aid cuts. But Mokhothu Makhalanyane, chairperson of Lesotho’s legislative health committee, said the impact is huge, estimating the country was set back at least 15 years in its HIV work.

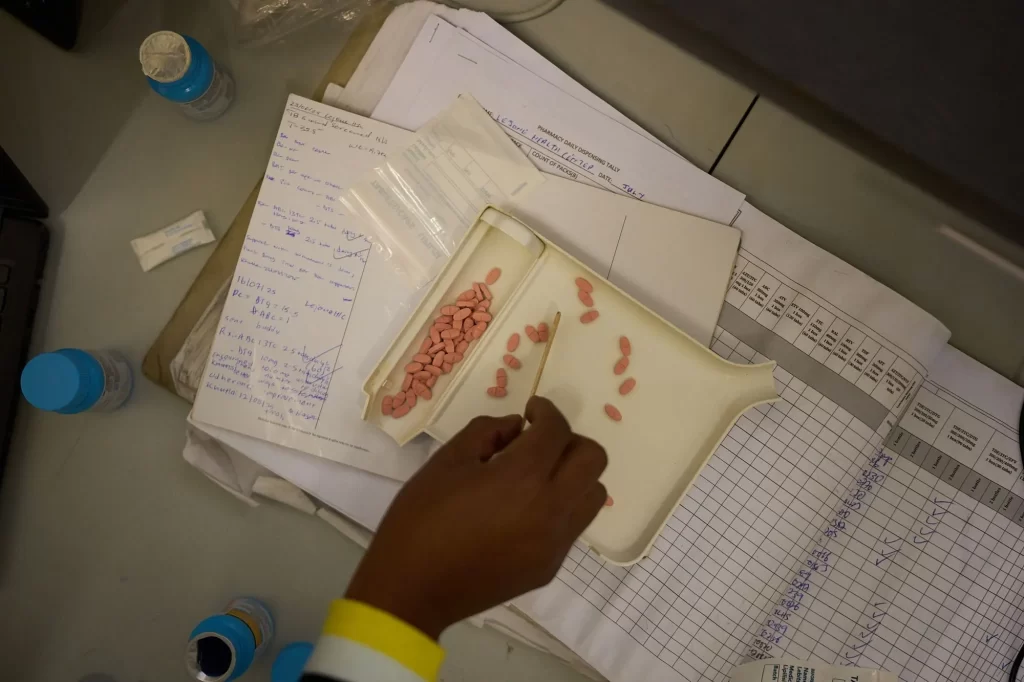

A pharmacist counts HIV medicine inside a clinic in Ha Lejone, Lesotho, July 16, 2025.

HIV medication is seen on a shelf inside a clinic in Ha Lejone, Lesotho, July 15, 2025.

“We’re going to lose a lot of lives because of this,” he said.

Lesotho reached a milestone late last year — UNAIDS’s 95-95-95 goal, with 95% of people living with HIV aware of their status, 95% of those in treatment, and 95% of those with a suppressed viral load. Still, the nation must care for the estimated 260,000 of its 2.3 million residents who are HIV-positive.

Overall, Lesotho and even global HIV efforts accounted for small parts of the United States’ massive international aid efforts. USAID spent tens of billions of dollars annually. Its dismantling has rocked the lives of millions of people in low- and middle-income nations around the world.

For patients, ‘this has been the most difficult time’

Slide 3 of 5.

For many in this mountainous country and elsewhere, a positive HIV test 20 years ago was akin to a death sentence. If untreated, most people with HIV develop AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. At the height of the epidemic in 2004, more than 2 million people died of AIDS-related illness worldwide — 19,000 in Lesotho, UNAIDS estimated.

In 2003, the U.S. launched the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. PEPFAR became the largest commitment by any nation to address a single disease, and its main implementing partner was USAID. PEPFAR became so important and well known in Lesotho and other countries that health professionals and residents use the term as shorthand to refer to any HIV aid.

When foreign assistance was frozen, Lesotho lost at least 23% of PEPFAR money, putting it in the top 10 countries for share of such funding cut, according to the Foundation for AIDS Research.

A cemetery where hundreds of people who died of AIDS are buried in Maseru, Lesotho, July 20, 2025.

Mapapali Mosoeunyane, 62, poses for a portrait inside her home in Ha Koloboi, Lesotho, July 12, 2025.

Mapapali Mosoeunyane is among Lesotho residents who credit PEPFAR with helping save them. After learning she had the virus in 2009, she was certain dying was just a matter of time. Neighbors gossiped, she was fired, and she considered giving up her two young sons for adoption.

But around 2013, she got access to antiretroviral medication — which suppresses HIV levels in the blood, with the potential to bring it to undetectable levels. In 2016, Lesotho was the first African country to “test and treat all” — everyone who tested positive was prescribed ARVs. That work, officials say, was possible because of PEPFAR.

Today, 62-year-old Mosoeunyane leads a peer support group in her village, Ha Koloboi. Neighbors ask for advice and trust her with their green medical booklets, where they record medical history, viral load, symptoms and medications.

Lately, the group mostly worries — about the future, losing medication access, getting sick again.

“This has been the most difficult time for me,” Mosoeunyane said.

Many in Mosoeunyane’s group wish Trump himself could hear their concerns.

“Trump’s decision is already translating into real life,” said Mateboho Talitha Fusi, Mosoeunyane’s friend and neighbor.

The worries span Lesotho society: from rural to urban, low to middle income, patients to officials. Many Basotho – as people in Lesotho are known – feel hopeless.

A woman passes a barber shop with men sitting inside at the end of the day in Maseru, Lesotho, July 18, 2025.

Boys stand outside their homes after a day of work in Mafeteng, Lesotho, July 12, 2025.

Since aid was cut, confusion and changes haven’t stopped

When Trump dissolved USAID, Lesotho leaders said they tried to talk to U.S. officials, even through their South African neighbors after failing to connect directly. But, they said, they got more information from news reports.

For Lisebo Lechela, a 53-year-old sex worker turned HIV activist and health worker, the news was fast and blunt. Days after Trump’s order, she was about to distribute medication, but a call from her boss interrupted her.

“Stop work immediately,” she was told.

Lechela’s organization, the USAID-funded Phelisanang Bophelong HIV/AIDS network, had drop-in centers at gas stations where sex workers could seek services. Workers set up tents outside bars with condoms and the prevention medication known as PreP. Teams delivered medication directly to patients who wouldn’t step foot in public health clinics, for fear of discrimination.

Lisebo Lechela, 53, an HIV-positive sex worker, poses for a portrait in her house in Maputsoe, Lesotho, July 17, 2025.

Lechela’s group earned the trust of the skeptics and the stubborn. All that work is gone, she fears.

She still gets calls from people desperate for services and refills. She does what she can, and their stories haunt her.

Among them is a textile factory worker who turned to sex work at night to support her three children. She used to take PrEP and isn’t sure how she’ll protect herself. Most clients won’t use condoms, she said, some turning violent if sex workers insist.

“I have to put bread on the table,” said the woman, speaking on condition of anonymity because her husband, who works in South Africa, wouldn’t approve of her sex work. She can’t miss a day of factory work to wait in line at a clinic.

Visiting the woman at home, all Lechela could do was demonstrate how to use a female condom – and hope her clients wouldn’t notice or protest.

A 47-year-old sex worker who spoke to AP on condition of anonymity because her husband wouldn’t approve of her work, poses for a portrait in Maputsoe, Lesotho, July 17, 2025.

With nearly all community groups and local organizations like Lechela’s closed and 1,500 health workers fired, some Lesotho officials see overdue signs that their nation and others must stop relying on international aid.

“This is a serious wake-up call,” said Makhalanyane, the health committee chair. “We should never put the lives of the people in the hands of people who are not elected to do that.”

Rachel Bonnifield, director of the global health policy program at the Center for Global Development, called the Trump administration’s new vision for PEPFAR — with funds sent directly to governments rather than through development organizations — ambitious but high-risk.

“It is disrupting something that currently works and works well, albeit with some structural problems, in favor of something with high potential benefits … but is not proven and does not currently exist,” she said, noting that U.S. House Republicans recently said they’d like to see PEPFAR funding cut in half by 2028.

Lesotho had made recent gains

A woman dances to music inside a club in Maseru, Lesotho, July 20, 2025.

A woman smokes hookah inside a club in Maseru, Lesotho, July 20, 2025.

A man embraces a woman inside a club in Maseru, Lesotho, July 20, 2025.

UNAIDS’ main goal is to end the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat by 2030. Lesotho had made enough progress in reducing new infections and deaths to be on track, according to Pepukai Chikukwa, UNAIDS’s country director in Lesotho.

But after the aid cuts, things were “just crumbling,” she said, though she commended Lesotho’s efforts to mitigate the impact.

“Lesotho’s made progress one should not overlook; at the same time, it is still a heavily burdened country with HIV.”

Chikukwa was optimistic about the September announcement by the U.S. State Department — which took over implementation of foreign aid programs — that it would temporarily reinstate some lifesaving programs, including one to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission. She also applauded U.S. efforts to buy doses of a twice-a-year HIV prevention shot and prioritize them for pregnant and breastfeeding women in low- to middle-income countries, including Lesotho, via PEPFAR.

“We lost some ground,” she said. “The uncertainty was very high; now there is some hope.”

But it’s not clear how much the U.S. bridge programs will “close the gap,” added Chikukwa, even as she’s leaving Lesotho. Her role was eliminated because of the aid cuts. The South Africa UNAIDS office will oversee Lesotho, she said, but she wasn’t sure where she’d be reassigned.

In its email to AP, the State Department said Secretary Marco Rubio had approved lifesaving PEPFAR programs and urged implementers to resume their work. The email emphasized that officials will work with Lesotho to continue providing health foreign assistance, but didn’t give specifics about the amount of funding.

Lesotho funded only 12% of its own health budget. The U.S. and other foreign donors provided the rest. USAID alone accounted for 34% of the budget; the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 26%, according to a May presentation to lawmakers.

Health committee chair Makhalanyane said this month that it remains unclear how much U.S. aid is being reinstated, even if temporarily. There had been only verbal promises, nothing in writing, he noted, and hundreds of health workers who had been promised they’d be absorbed by the national health system remain unemployed.

Unlike other PEPFAR-supported countries, Lesotho funded medication for 80% of its HIV patients — a figure officials tout as they try to move toward a self-sustaining system. Still, the aid cuts sparked panic over supply and distribution.

Lesotho regularly gave patients a six- to 12-month supply to help its mobile population, including many who work in South Africa, stick with treatment. But when the cuts were announced, some nurses gave out even more drugs than usual.

Nurses were told to cut back. Patients grew alarmed.

Miner Monyamane said he got a three-month supply, not his usual 12. So instead of continuing to work in South Africa, he decided to remain in his small village of Thaba-Tsoeu Ha Mafa. Like many miners, he chose his health over a job and steady paycheck. He fears diseases such as tuberculosis — a leading cause of death in Lesotho, attributed to weakened immune systems — may creep up on him if he interrupts treatment.

‘You can’t just hang a shingle’

The Rev. Khethang Manyarela poses for a portrait inside his home in Maseru, Lesotho, July 20, 2025.

A man prays inside a church during a ceremony in Maseru, Lesotho, July 20, 2025.

The system propped up by foreign aid was always meant to be temporary. But public health experts say the shift to Lesotho and other countries becoming self-reliant should have been gradual.

At the United Nations General Assembly last month, Lesotho Prime Minister Samuel Matekane acknowledged the threat posed by declining foreign aid but fell short of pointing fingers. He said Lesotho is mobilizing domestic resources to address gaps.

But Catherine Connor, of the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, emphasized that “any step backward creates a risk of resurgence.”

In the 16 years her organization has worked in Lesotho, HIV transmission from mother to child dropped to about 6% from nearly 18%. Lesotho’s government should get credit, Connor said, but her group and others were key in targeting children’s treatment and prevention.

Since 2008, Connor’s group received more than $227 million from the U.S. for Lesotho programming, USASpending.gov data shows. This fiscal year, about half the work it planned has been terminated.

“You can’t just hang a shingle that says, ‘Get your ARVs here,’ and people line up,” Connor said.

Most at risk, she and others stressed, are children.

As of late August, half of PEPFAR funding targeted toward children in Lesotho was terminated, and 54% of infants tested for HIV before their first birthday in fiscal year 2024 were evaluated by programs that had been cut, according to Foundation for AIDS Research data.

“When a child never gets diagnosed, it feels like a missed opportunity,” Connor said. “When a child who was receiving treatment stops getting treatment, it feels like a crime against humanity.”

A lack of trust in what remains of the system

Rethabile Motsamai, 37, who lost her job as an HIV counselor poses for a portrait in Maseru, Lesotho, July 20, 2025.

Rethabile Motsamai, a 37-year-old psychologist and mother of two, has worked since 2016 for aid-funded organizations. But months ago, her HIV counselor role was eliminated.

She worries for the populations her work served.

“They have to travel for themselves to the facilities — some are very far,” she said, adding that she knows some patients simply won’t try. “They’ll just stop taking their medication.”

Those who do make the trip may be met with a dead end. Clinics have continued to close.

For Lechela — the longtime activist — the upheaval and loss of her job means she once again depends solely on sex work. As she walked by the closed doors of her former clinic, passersby stopped and begged her to reopen.

“I don’t trust anyone else,” a young woman called out. “Please! Please!”

Lechela smiled but couldn’t bring herself to reply. Like many here, she simply has no answers.

. . .

- “Trump Has Made the Epstein Saga a Case Study in Manipulation”, The New York Times

- “SA likely to support UN General Assembly resolution demanding Russia return abducted Ukrainian children”, The Daily Maverick

- “Honduran Drug Kingpin and Former President Walks Free After Trump Pardon”, National Review

- “Pete Hegseth’s Caribbean lawlessness”, The Washington Post

- “Pete Hegseth Needs to Go—Now”, The Atlantic

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017